Photo © 2024 Thee Arizona times

A lawsuit filed by the US Justice Department lawsuit alleges that Alabama, which has more than 26,000 inmates in its severely overcrowded and understaffed prisons, fails to prevent violence and sexual abuse against its inmates as well as to provide safe conditions and protect them from excessive force by prison staff.

Currently, the deadliest jail in the nation is Alabama’s men’s cells. 19 individuals may have died from drug-related causes in 2021, 6 men committed suicide, and 11 men were murdered in Alabama jails. As a result of the same circumstances, there were at least 110 deaths from drugs and violence in four years, including 25 in 2020, 27 in 2019, and 22 in 2018. The information was assembled from press accounts and verified independently by jail authorities, coroners in the county, medical examiners, and autopsy records.

And it appears that the state’s horrifying mass inmate mistreatment does not seem to end even with death.

Montgomery County Circuit Court cases filed this week present the state Department of Corrections and the University of Alabama at Birmingham with serious allegations from the relatives of five prisoners whose organs were taken out and allegedly retained against their will.

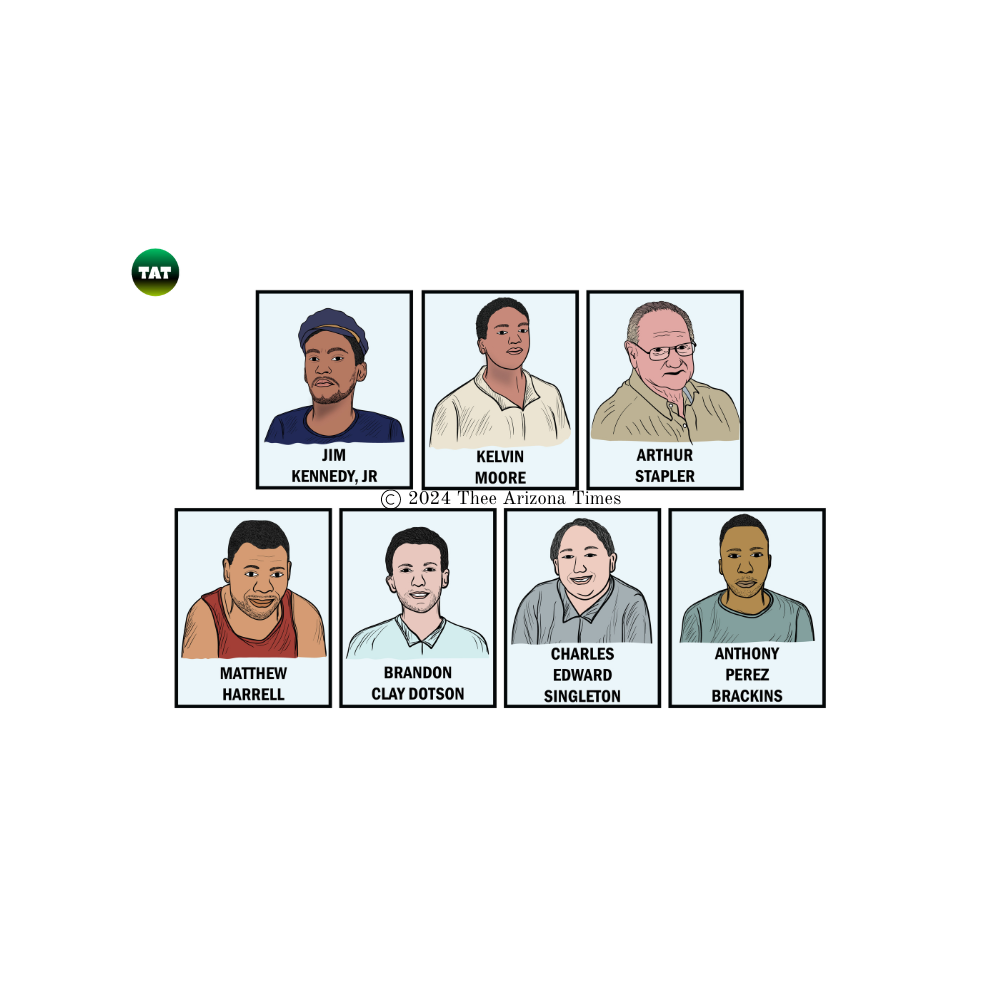

First Case: Jim William Kennedy Jr., a 67-year-old prisoner serving a 300-year sentence for rape, sodomy, and abduction, passed away on April 13, 2023, in the Limestone Correctional Facility in Harvest, Alabama. About four days later, a prison priest informed his family of his passing, the lawsuit claims.

As reported to CNN, the funeral home called a family member to let them know that the man’s internal organs were missing while they were getting his body ready for burial.

Did you all know he returned without his organs? Sara Kennedy remembered being informed. “Heart, liver.” each of the main organs. They vanished.

Sara Kennedy asked UAB and prison authorities to provide information. She remarked, “I had a lot of questions.”

She covertly taped the six-minute phone call she had with a UAB autopsy department to request the return of her brother-in-law’s organs. A supervisor from the UAB autopsy department was heard on the recording stating that they often bury victims without their bodily organs.

“I’ll tell you something now. UAB is a teaching institution and therefore any teaching institution that performs an autopsy also retains its organs,” he stated.

“We haven’t given the jail our consent to turn over his body for research purposes.” According to CNN, Sara Kennedy informed the supervisor, “And we want those organs back.”

The supervisor informed her over the recorded conversation, “We’ve never had this request done before.”

The family had not allowed for the organs to be retained, according to Marvin Kennedy, who had his brother’s power of attorney.

Of UAB and jail officials, Marvin Kennedy remarked, “They made the decisions for you without seeking your permission in different areas.”

Second Case: Anthony Perez Brackins, 36, passed away in Limestone on June 28, 2023, when he was serving a 21-year sentence for armed robbery, according to his mother Susie Duncan, and sister Letesha Brackins. An unintentional drug overdose was reported as the cause of death.

According to Duncan and Brackins, the family was notified by a funeral home that the body had been “emptied” of all organs following an autopsy conducted at UAB. Duncan stated her son’s organs were not included in the cremation. According to Duncan, UAB did not request her permission to preserve the organs, and he was not an organ donor.

Third Case: At Limestone on July 21, 2023, 42-year-old Kelvin Lamar Moore, who was convicted of attempted murder and attempted burglary, passed away. Moore was serving a life sentence without the possibility of release.

According to Andscape, on July 21, 2023, Agolia Moore received a call from the chaplain of the Harvest, California-based Limestone Correctional Facility informing her that her 43-year-old son Kelvin Moore, with whom she had chatted over the phone for around 90 minutes was dead from a fentanyl overdose.

Moore’s hometown is around 350 miles away from the jail, and his body was transported there six days later. Moore’s body was initially transported to the University of Alabama in Birmingham, which performs autopsies for the Alabama Department of Corrections because he passed away while being held in jail.

Upon receiving his body from his relatives, the mortician found that the majority of his internal organs had disappeared. A scarlet viscera bag containing what UAB claimed to be his organs was later given to the relatives. With the bag, Moore was laid to rest.

Simone Moore recollected their 82-year-old mother saying: “You can’t even die anymore, people still mistreat and rob you even when you’re dead, taking away your organs.”

Kelvin Moore’s family is determined to seek justice, as they believe that his case should serve as a warning and advocate for transparency and consent in organ retrieval from deceased inmates.

Fourth Case: Arthur Olen Stapler passed away on September 23, 2023, after spending ten years at the Hamilton Aged and Infirmed Centre due to allegations of child sex assault. He had congestive heart failure, according to the autopsy report.

Upon conducting an autopsy, the son-hired private pathologist found that his organs were replaced with “an empty cavity.”

Billy, Stapler’s kid, compared it to a nightmare movie from which he is unable to wake up.

“Nothing was there,” stated Billy Stapler.

Through a phone communication with the supervisor of the UAB autopsy department, Stapler also requested the repatriation of his father’s organs.

“Where are his remaining organs? Billy Stapler stated, “And he tells me that they might have been thrown away.” And I wonder, how are organs disposed of? … Why even did you remove them from him?

Stapler’s family didn’t learn that his brain and heart were in plastic viscera bags until they got in touch with the University of Alabama in Birmingham, one of the organizations that does autopsies for the criminal justice system. Parts of the internal organs, including the lungs, were recovered, but not all of them.

Fifth Case: In 2021, Charles Singleton, 74, passed away in a Tennessee hospital while serving time at the Hamilton Aged and Infirmed jail. In an affidavit, his daughter stated that Singleton’s corpse was brought to UAB for an autopsy after his passing. Singleton’s brain and other organs were gone, the funeral director discovered after the examination and when his body was sent to a funeral home in Pell City.

When Singleton’s daughter phoned UAB to return the organs, she was told that organ removal was legally allowed and that it was standard practice.

All the families involved claimed that UAB’s Pathology Department had not provided them with clear explanations for the removal and retention of those organs.

Lauren Faraino, a human rights attorney in Birmingham, is looking into the missing organ issue. According to her, the families she is defending in the five lawsuits have stated that none of the prisoners donated their organs, nor were their relatives contacted to obtain permission to keep the organs.

According to lawyer Lauren Faraino, there appears to be a pattern of abuse in these cases. She contends that for years, the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), which performs autopsies for the jail system, has been removing inmates’ organs without getting permission from their families.

In reaction to the claims, a UAB official issued a statement.

“Autopsies are only performed after receiving authorization,” said a UAB official as per Alabama Media. The autopsy practice employs qualified medical professionals who hold certification from the American Board of Pathology, and it is accredited by the College of American Pathologists.”

“The authorization papers not only grant permission for the autopsy but also express agreement for the removal of organs or tissues for diagnostic or other tests, including ultimate disposal,” said UAB in the statement, adding that privacy rules prohibit discussion on individual autopsy results.

“When a prisoner dies, their body is either taken to the University of Alabama at Birmingham or the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences for an autopsy. This depends on many circumstances, such as the inmate’s location and whether or not the death was suspicious, illegal, or out of the ordinary,” the corrections department said in a statement.

The UAB’s autopsy authorization form, which CNN was able to obtain, gives a jail warden the authority to approve the autopsy and the eventual disposition of an inmate’s organs “without limitations.” Meaning unless instructed differently, UAB is free to preserve and discard the organs as it deems suitable.

The warden is certified as the legally designated representative under an autopsy agreement between corrections and the UAB Board of Trustees that dates back to approximately 2005. As such, “I am legally qualified to authorize the completion of an autopsy and the removal of organs or tissues for additional research on the said inmate.”

Accordingly, the autopsy authorization form states that the prison warden can give permission for an autopsy to be carried out as well as remove any organs or tissues necessary for diagnostic or other testing, including final disposition.

Brendan Parent, JD, a lawyer, associate professor of bioethics in the division of medical ethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, director of transplant ethics and policy research, and dual appointment in surgery said that;

“A prison warden doesn’t have ownership or property rights over the bodies of inmates. Therefore, the laws that are in place to safeguard the family’s ability to express their preferences for donations and for burial or cremation still stand.”

Thus, the claims said, “the defendants’ heinous acts are nothing less of a grave robbery and mutilation.” Allegations against state institutions include fraud, conspiracy, carelessness, unjust enrichment, unauthorized body part donations, and neglecting to inform next of kin when keeping organs, among other offenses.